Lizzie Borden took an axe, and gave her mother forty whacks. When she saw what she had done, she gave her father forty-one. Or so the story goes, at least. On August 4, 1892, Borden’s father and stepmother were found slaughtered in their home in Fall River, Massachusetts. The evidence pointed to Borden: The couple was murdered at home, on a busy street in the middle of the day, with no one entering or leaving the house, and Borden was home at the time. The resulting trial captivated the media.

First, a Portuguese immigrant was arrested; he was innocent, and soon released, but it seemed to confirm the widespread feeling that the crime itself was not something a woman could have done. Borden was interviewed extensively but never became a suspect until her story began to change. The media battled over whether she was innocent, and so did women’s groups and other Borden supporters. After a two-week trial, she was found not guilty.

On June 25, 1906, railroad heir Harry Kendall Thaw murdered famed architect Stanford White on the rooftop restaurant and theater of Madison Square Garden. Years earlier, the married White had raped the woman who would become Thaw’s wife, Evelyn Nesbit, who was just 16 at the time. Plagued by jealousy and mental illness, Thaw shot White three times during the finale of Mam'zelle Champagne, the show being performed at the rooftop theater. According to witnesses, Thaw screamed, “He ruined my wife!”

The ensuing trial electrified the East Coast press, which was, by 1906, a certified mass media machine. Pittsburgh and New York papers ran wall-to-wall coverage. Thomas Edison's studio even produced a nickelodeon film about the murder just one week after it occurred.

Because of the surrounding front-page frenzy, Thaw's trial is often cited as the first “trial of the century” by legal scholars and media historians (though the term wasn’t used until later to describe the events in retrospect). The Library of Congress dubs it “the first trial of the century” in its Chronicling America: American Historic Newspapers collection.

Both the district attorney and Thaw’s first lawyer wanted an insanity plea, but Thaw’s family refused to sully their name in such a manner. Their lawyer argued Harry was a victim of a very specific type of temporary insanity: "dementia Americana.” This was defined as insanity caused by a violation of "the sanctity of his home or the purity of his wife."

A deadlocked jury meant that the trial would be repeated, and the breathless press attention would continue. Thaw was found not guilty by reason of insanity after the second trial and was effectively sentenced to life at a facility for the criminally insane. He later would escape by simply walking out the front door and into a waiting car headed for Quebec. After his eventual extradition from Canada, Thaw underwent a third trial, where he eventually was found not guilty and also sane.

Thaw and Nesbit divorced, and just two years later, Thaw was arrested again for whipping a 19-year-old boy. He was again sent to an insane asylum, and was freed in 1924. Harry K. Thaw died a free man in Miami in 1947.

The media sunk its teeth into the trials of Harry K. Thaw, and a formula was born: Sensational court cases featuring lurid details and a compelling cast of characters sold newspapers. When American union pioneer “Big Bill” Haywood was tried in 1907 for the assassination of Frank Steunenberg, a former governor of Idaho, newspapers around the country knew they didn’t have to wait long to find a case that could match the drama of Thaw’s.

Haywood’s defense team featured famed Chicago lawyer Clarence Darrow, and the trial marked the legendary litigator’s introduction to the national stage. As Harry L. Crane wrote in a 1907 issue of the Idaho Statesman, the trial “will be a trial of greater importance than any other criminal trial in the history of this country, of more importance than the Thaw trial.” Reporters from across the country relayed Darrow's impressive tactics to their readers. It was “one of the great court cases in the annals of the American judiciary,” John W. Carberry wrote in the Boston Globe. Socialist newspaper the Daily People dubbed it “the greatest trial of modern times.”

Darrow’s skilled defense and his team’s comprehensive cross-examination of the government’s star witness resulted in the jury issuing a verdict of not guilty.

In 1920, Italian immigrants Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco were arrested for killing two people during a robbery of a shoe factory in Braintree, Massachusetts. The case looked to be open-and-shut—police found a firearm and ammunition on Sacco that matched the casings found at the scene of the crime—and the two were convicted in 1921. Circumstances surrounding the men, including well-funded support during their appeals, meant that their saga, widely covered by the press, would continue for another six years.

Sacco and Vanzetti were anarchists, and their conviction sparked retaliation in the form of bombings in the U.S. and at American embassies abroad. The increased attention the case received wound up shedding light on the shakiness of the trial and the prosecution's reliance on testimonies from untrustworthy witnesses. Sympathetic parties—both radical anarchists and left-leaning moderates—raised money for a defense fund. This sparked multiple appeal efforts that lasted until 1927. Throughout this period, as intriguing new evidence came to the fore, both the national and international press closely followed the developments.

As future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter wrote in The Atlantic in 1927, "The fact is that a long succession of disclosures has aroused interest far beyond the boundaries of Massachusetts and even of the United States, until the case has become one of those rare causes célèbres which are of international concern."

The appeals were unsuccessful, and the two men were executed in 1927.

The 1920s saw a number of remarkable criminal trials, but none rocked Hollywood so violently as the trial of one of its biggest film stars, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. The portly comic actor threw a party in San Francisco over Labor Day weekend in 1921. Within days, an actress at the party named Virginia Rappe was dead and Arbuckle was accused of manslaughter.

He insisted he was innocent, and there was nothing to show he committed a crime beyond the testimony of a notorious woman-about-town named Maude Delmont. She wasn’t an ideal witness—some in Hollywood had nicknamed her Madame Black, since she had a habit of entrapping rich men in sexual hijinks and then blackmailing them. Delmont claimed Arbuckle had crushed Rappe to death when he raped her; William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers ran regular updates from the courtroom as the first and second trials ended in deadlocked juries. In his third trial, Arbuckle was acquitted, but his reputation never recovered from the media circus.

Beulah Annan, a married, hard-partying Jazz Age kid, was accused of shooting her boyfriend, Harry Kalstedt, in her apartment and then playing a foxtrot record for hours while he bled to death. Cabaret singer Belva Gaertner was also married and accused of murdering her boyfriend, Walter Law, when he was discovered dead in her car, and she was found with bloody clothes. Though the women didn’t know each other, their sensational murder trials both took place in 1924 in Chicago, and both trials were covered by reporter Maurine Dallas Watkins for the Chicago Tribune. Both defendants were acquitted.

Later, Watkins attended what would become Yale School of Drama and wrote a play based on the two murders and subsequent trials. The play would become known as Chicago. After her death in 1969, Bob Fosse adapted it as the Broadway musical Chicago: A Musical Vaudeville in 1975, and the rest is history.

Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb were two well-to-do students at the University of Chicago. Obsessed with the idea of committing a “perfect crime,” the two abducted Bobby Franks, a 14-year-old boy living in the Chicago suburbs, on May 21, 1924. They then murdered Franks in a car rented with a fake name and dumped his mutilated body near the Indiana border.

While the two had concocted what they thought to be a meticulous plan, it was undone when Leopold’s eyeglasses were found near Franks’s body. That specific type and design of eyeglass frame had been sold to only three people in all of Chicago, and Leopold was one of them. The two were brought in for questioning, and soon Loeb confessed to the murders.

The trial became a magnet for media frenzy, not least because the families hired none other than Clarence Darrow to lead the defense. Knowing that the jury pool had been tainted by relentless newspaper coverage, Darrow managed to avoid a jury trial (and likely death penalty conviction) by having his clients plead guilty, which would leave the sentencing up to the judge. Darrow used the case to highlight and question aspects of American culture and its justice system as they pertained to punishment and the supposed worth of human life. This came in the form of a 12-hour closing argument, one that touched on everything from morality and nature to the works of Friedrich Nietzsche. The marathon speech is still revered by legal scholars because it helped Darrow do the impossible: spare the lives of two killers who were guilty as sin. Loeb and Leopold were both sentenced to life imprisonment. Loeb was later murdered by another inmate; Leopold was paroled 34 years later and lived out his life in Puerto Rico.

The 1925 trial of John Thomas Scopes briefly turned the Rhea County Courthouse in Dayton, Tennessee, into the epicenter of a heated cultural battle. Scopes, a substitute biology teacher, was arrested for violating the Butler Act, a Tennessee law that banned the teaching of evolution in schools. Scopes was well aware that the case would be used as a proxy suit conducted by various interest groups to garner attention (as an ACLU figure had said, “We are looking for a Tennessee teacher who is willing to accept our services in testing this law in the courts”), and publicity for the trial soon followed in a big way.

The small Tennessee county would host the two biggest lawyers in the country: Clarence Darrow (again), who was on the team that represented Scopes, and William Jennings Bryan, a former presidential candidate, who was part of the prosecution.

The proceedings were covered by the dozens of gathered reporters representing papers from around the country. Famous journalist H.L. Mencken provided colorful correspondence from Tennessee for The Baltimore Sun, and supposedly coined the term Monkey Trial. It was the first trial in America to be broadcast on national radio. (Mencken also gave coined lasting contribution to the language at around the same time: “Bible Belt.”)

The proceedings were packed with dramatic moments, including Darrow calling Bryan to the stand to question him on the veracity of the Bible. The result has been called “the most amazing courtroom scene in Anglo-American history.”

The jury found Scopes guilty, though the attention brought on by the trial increased scrutiny on the Butler Act and laws like it. The publishers of The Baltimore Sun, for their part, paid Scopes’s $100 fine.

In 1922, the corpses of Eleanor Mills and Edward Hall were found in a field in New Jersey, their bodies positioned intimately next to each other with ripped-up love letters sprinkled between them. Hall's widow and her two brothers were charged with the murders, and the tawdry case became a magnet for the press (Hall was a minister; Mills sang in the church choir).

In 1999, The Washington Post’s Peter Carlson pointed to the trial following the murders as an example of a “trial of the century” that was soon forgotten. At the time, however, it was the biggest news story in the entire country. The proceedings were dubbed “the trial of the century” by legendary newsman Damon Runyon, and the small town’s courthouse attracted “300 reporters, requiring the phone company to bring in a special switchboard and 28 extra operators.”

“The key witness,” Carlson wrote, “was an eccentric, mule-riding female hog farmer, known to tabloid readers as 'the Pig Woman.’…Ah, the Pig Woman! Who could ever forget the Pig Woman?” The witness, who was hospitalized at the time, was wheeled into the courtroom in her bed and testified from there.

All three suspects were acquitted.

On March 1, 1932, the infant son of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh went missing from the family's home in New Jersey. Two months later, the baby’s remains were discovered, and the kidnapping case became a two-year murder investigation, eventually leading to a suspect: German immigrant Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

At the time, the kidnapping was covered in the press as the “crime of the century,” and Hauptmann’s ensuing murder trial was dubbed the “trial of the century.” A media circus, the likes of which had never been seen, besieged the Hunterdon County Courthouse in New Jersey. Adding to the hoopla were sound cameras, used for the first time by the press in the coverage of a criminal trial. H.L. Mencken, again on the scene, called it “the biggest story since the Resurrection.”

The press coverage went so overboard and interfered with the proceedings to such a great affect that the American Bar Association issued a report begging for legislation to curb the media. “Newspaper interference with criminal justice always appears most flagrantly in celebrated criminal cases,” the report read. Citing the Hauptmann case, it complained that the press “hippodromed” and “panicked” the proceedings.

Hauptmann was found guilty and sentenced to death. According to The New York Times, he based his appeal “on the grounds that [he was] actually tried and condemned by the press.”

Daughter of famous railroad heir Reginald Vanderbilt and his much younger socialite wife Gloria Mercedes Morgan, Gloria Vanderbilt achieved celebrity status just by being born. Her father died after a life of heavy drinking when Gloria was 18 months old, and both she and her immense trust fund went to her hard-partying mother. In 1934, when Gloria was around 10, her aunt Gertrude Whitney—Reginald’s sister, who was one of the richest woman in America at the time—effectively kidnapped her niece because she viewed the mother as being unfit, sparking a scandalous trial tailor-made for New York’s front pages.

Gertrude’s legal team hammered home the lurid details of Gloria Morgan’s so-called “debauched” lifestyle in front of the more than 100 reporters present in the courtroom throughout the trial. Papers were unrelenting, eager to relay specifics about the young mother’s “alleged erotic interest in women.”

After almost two months of mud-slinging, the court awarded Gertrude Whitney custody of her niece. Gloria Vanderbilt’s mother was allowed visitation on the weekends. One newspaper summed up the verdict with parody song lyrics, highlighting the kind of devastating, compassion-free coverage readers had come to expect:

“Rockabye baby, up on a writ, Monday to Friday Mother’s unfit. As the week ends she rises in virtue; Saturdays, Sundays, Mother won’t hurt you.”

The military tribunals of 22 Nazi leaders for war crimes and crimes against humanity were held between November 20, 1945, and October 1, 1946, and they proved to be greater in consequence and profundity than perhaps any other trial in history. While the purpose of the trials was to bring high-ranking Nazi officials to justice, they also presented a chance to fully impart to the world the breadth and grim severity of Nazi Germany’s actions leading up to and during World War II.

Considering many Nazi leaders (including Hitler) had died by suicide at the war’s end, those present at the tribunals represented some of the highest-ranking officials who could answer on behalf of their government.

Unlike previous “trials of the century,” there was little room (or need) for sensationalism in the coverage of the Nuremberg tribunals. On February 21, 1946, The New York Times touched on this in a short editorial, printed on page 20: “When a running story in a newspaper begins to be more of the same and doesn’t surprise people any more,” the piece reads, “it is taken off the front page and put inside somewhere. This practice follows a sort of natural law of journalism. Just now it gives the Nuremberg trials a back seat. We learned a while back that the defendants were believed to be responsible for at least 6 million murders. What we have been getting in the past few days are details about some of these murders … [t]hey are not new, because the evidence had already run through every conceivable bestiality. But it would be well if we paid attention to them.”

In 1951, two years after the Soviet Union detonated their first atomic bomb test, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were tried and convicted for conspiracy to commit espionage by giving nuclear secrets to the U.S.S.R. David Greenglass (Ethel’s brother), a machinist who worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory, testified that he gave Julius Rosenberg documents relating to the U.S.’s work on the atomic bomb. Ethel and Julius both denied any involvement, but their month-long trial concluded with a guilty verdict and the death penalty. The Rosenbergs were the only American citizens executed for espionage during the Cold War; they were killed by the electric chair on June 19, 1953.

Upon sentencing the Rosenbergs to death, Judge Irving Kaufman told the couple, “I consider your crime worse than murder. Plain deliberate contemplated murder is dwarfed in magnitude by comparison with the crime you have committed. In committing the act of murder, the criminal kills only his victim … Indeed, by your betrayal you undoubtedly have altered the course of history to the disadvantage of our country. No one can say that we do not live in a constant state of tension.”

Naturally, the trial helped accelerate Cold War paranoia in America. Julius Rosenberg’s former membership in the American Communist Party was used by anti-communist politicians as proof of left-wing subversion within U.S. borders. Supporters of the Rosenbergs—or people who had merely objected to the trial’s haste or the harshness of the sentencing—were painted in the press as part of a growing communist movement.

According to the Federal Judicial Center, “The Chicago Daily News was the only major mainstream American newspaper to advocate clemency for the Rosenbergs,” and that, throughout the trial, “[n]ewspaper stories often relied on Department of Justice or FBI press releases for the bulk of their source material, and sensational headlines … helped to foster a public perception that they were dangerous traitors bent on helping a bitter enemy to destroy the United States.”

On July 3, 1954, osteopath Sam Sheppard fell asleep while watching TV with his pregnant wife in their home in the Cleveland suburbs. Awoken by his wife’s screams, Sheppard says he went upstairs to investigate and was knocked unconscious by a mysterious intruder. When he came to, his wife was dead, and he would soon be charged with her murder.

Local and national media went wild with the case—to the point of tampering with it. The Cleveland Press pushed and pushed for the state to take action against the doctor. “WHY NO INQUEST? DO IT NOW, DR. GERBER,” read one headline aimed at county coroner Sam Gerber. As if at the paper’s command, the coroner then performed a public inquest with Sheppard in a crowded high school gym. When that wasn’t enough, the Press ran a front-page editorial demanding that police arrest Sheppard. “QUIT STALLING—BRING HIM IN,” screamed the headline. Sheppard was arrested that night.

Sheppard was convicted for the murder of his wife in the second degree in 1954. He successfully appealed the ruling in 1964 and, in 1966, the United States Supreme Court reversed the murder charge. Their decision placed the blame, in part, on the media. The ruling states that “[t]he massive, pervasive, and prejudicial publicity attending petitioner’s prosecution prevented him from receiving a fair trial.”

In 1998, 28 years after Sheppard died a free man, new DNA evidence was released that implicated the Sheppards’ window washer for the murder. Following a second trial, Sheppard was found not guilty.

Like the Nuremberg tribunals, the trial of Adolf Eichmann captured the world’s attention due to the unthinkable severity of the crimes committed. Eichmann was a high-ranking Nazi SS lieutenant colonel whose decisions were key to shaping the Holocaust. After World War II he managed to escape to Buenos Aires, where he lived comfortably for around a decade until his capture in 1960 by a team of Israeli security and intelligence agents.

After being brought to Israel, Eichmann stood trial for a number of crimes, including crimes against humanity. The 1961 proceedings were videotaped and broadcast by press outlets around the world, making it one of the first truly international media events. This was intentional; the trial served as a reminder of the suffering endured by victims of the Holocaust, given that, at the time of the trial, the events of World War II had concluded a full 16 years prior.

Notably, the trial was heavily broadcast in Germany and covered by hundreds of German journalists in Israel. “There was a lot of watching, and it changed the discussion about the Holocaust,” philosopher Bettina Stangneth told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

At the end of the trial, Eichmann was found guilty of multiple charges and was sentenced to death.

The U.S. Justice Department charged eight antiwar activists with conspiracy and other federal charges stemming from a violent clash with police at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago [PDF]. One defendant, Bobby Seale, had a mistrial, leaving seven defendants who by-and-large knew each other only through their shared objection to the Vietnam War. The “Chicago Seven” trial lasted for several weeks and included testimony from the biggest countercultural intellectuals and celebrities of the late ‘60s, including Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, Judy Collins, Jesse Jackson, and others.

The raucous legal proceedings—depicted in the 2020 film The Trial of the Chicago 7, with Sacha Baron Cohen playing the role of Abbie Hoffman—involved Judge Julius Hoffman convicting each defendant and their two attorneys on a total of 159 counts of contempt. Nevertheless, the jury acquitted all seven of their charges of conspiracy, while five were convicted of traveling across state lines with the intent to riot. Those convictions were reversed during the appeal process.

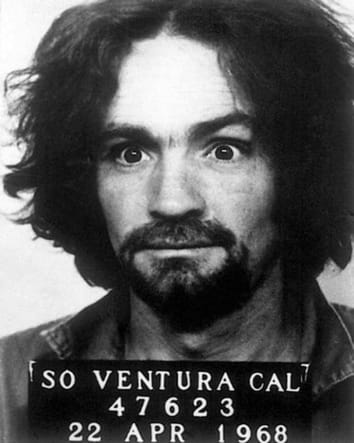

Lifelong criminal and aspiring musician Charles Manson led a cult of devoted followers—known as the Manson Family—in California, and inspired them to commit at least eight murders over the summer of 1969 in the hopes of starting an apocalyptic race war. The violent nature of the killings combined with the group's twisted counterculture leanings and hippie looks made for a trial that would puncture a hole in the zeitgeist.

According to Manson prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi in his and Curt Gentry’s book Helter Skelter, “The bizarre nature of the crime, the number of victims, and their prominence—a beautiful movie star, the heiress to a coffee fortune, her jet-set playboy paramour, an internationally known hair stylist—would combine to make this probably the most publicized murder case in history, excepting only the assassination of President John F. Kennedy."

While Manson himself wasn't present during the murders, he had ordered his followers to perpetrate them and was charged accordingly. Their trial became nothing short of a circus. When Manson displayed all sorts of odd behavior during the proceedings, his disciples—both fellow defendants and uncharged Manson family members hanging outside and around the courthouse—followed, be it by shaving their heads or carving Xs into their foreheads.

American media dedicated their coverage to Manson’s bizarre antics, and he reveled in the attention, using violent outbursts in court to distract from the evidence brought against him. This is described, in detail, in Helter Skelter:

"With a pencil clutched in his right hand, Manson suddenly leaped over the counsel table in the direction of Judge Older. He landed just a few feet from the bench, falling on one knee. As he was struggling to his feet, bailiff Bill Murray leaped too, landing on Manson’s back. Two other deputies quickly joined in and, after a brief struggle, Manson’s arms were pinned. As he was being propelled to the lockup, Manson screamed at Older: ‘In the name of Christian justice, someone should cut your head off!’"

All five defendants were sentenced to death in 1971, though that was reduced to life in prison after California banned the death penalty.

Serial killer Ted Bundy was sentenced to death on July 30, 1979, after a much-publicized (and televised) trial riddled with strange events. Bundy was handsome, intelligent, well-spoken, and charismatic, all things that translated into his trial. He represented himself, he read Russian literature during slow moments in court, and eventually—days before his execution—confessed to his crimes. Before that, though, he escaped from jail twice and proposed and married his partner in the courtroom. The trail pulled in massive ratings from viewers who had trouble reconciling that such a charming person could be capable of such evil. Even the gathering of spectators outside his execution in 1989 was televised.

On August 20, 1989, brothers Lyle and Erik Menendez shot their wealthy parents to death. Over several years, three trials, and countless hours of media footage, the brothers were found guilty. Court TV, a new network in the early 1990s, dedicated itself to turning court cases into virtual sporting events. Each broadcast of the trial was followed by extensive coverage before and after, with every newscaster drawing their own conclusions about what actually happened. Most of whom said the brothers killed their parents for the insurance money and inheritances, while the Menendez brothers detailed extensive sexual abuse at the hands of their father. Today, Lyle and Erik are having a resurgence of popularity on TikTok with videos made from old news coverage.

Pamela Smart, a married 22-year-old teacher, carried on an affair with a local teenager named Billy Flynn. On May 1, 1990, Smart came home to find her husband Greggory shot to death. She was arrested in August, with the prosecution arguing that she had coerced Flynn and three of his friends to break into the home and kill her husband. The jury found all five conspirators were guilty in Gregg’s death. Smart was sentenced to life in prison, and the four boys received lesser sentences.

The media was all over the case, broadcasting all the trials live over previously scheduled programming. Later, there would be a made-for-TV movie, a feature film (To Die For, starring Nicole Kidman), and many true crime segments about the case. Smart still gives interviews, and still maintains her innocence.

On June 23, 1993, a manicurist named Lorena Bobbitt cut off her husband’s penis with a kitchen knife, drove away from their Manassas, Virginia, home with it still in her hand, and tossed it in a field before a friend called 911 to report the incident. She told investigators that her husband, John Wayne Bobbitt, had raped her that night. Meanwhile, police located the missing member and brought it to an area hospital, where John Wayne Bobbitt underwent a successful procedure to reattach it. “I thought the word would get around the hospital and it’d be forgotten in a day or two,” plastic surgeon David Berman told Washingtonian. “But it got picked up by the media almost immediately, and within 12 hours it kind of exploded on the world scene.”

Both Bobbitts were arrested, and during the spectacular trial—broadcast by Court TV—a history of physical and emotional abuse emerged. John Wayne Bobbitt was acquitted of a sexual assault charge, while Lorena Bobbitt was found not guilty of malicious wounding by reason of insanity stemming from the abuse. Since the sensational event, Lorena Bobbitt has maintained a low profile and has largely avoided publicity, while John Wayne Bobbitt has starred in two adult movies, been arrested on a number of charges, and generally tried to cash in on his unexpected notoriety.

By the time O.J. Simpson was put on trial for the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman—January 24, 1995—cable news was coming into its own. (CNN had been around for 15 years and Court TV had debuted just a few years prior. Fox News and MSNBC, meanwhile, wouldn't be launched for another year.) The 24-hour networks made a spectacle of the trial, broadcasting every detail for an obsessed country that couldn't get enough. Very real specifics of the case were treated like plot points from a shared text—the white Bronco, Bruno Magli shoes, the leather glove, Kato Kaelin, and DNA evidence, to name just a small few.

While the double murder had the makings of early "trials of the century" (celebrity suspect, shocking violence), cable news (as well as traditional press outlets) catapulted the case to unparalleled levels of nationwide attention. As Mark Crispin Miller, a professor of Media, Culture, and Communication at NYU, told the Washington Post, the Simpson trial served as a “harbinger of an entirely different media landscape — an event that preoccupies everyone full-time for months on end." From the white Bronco chase to Simpson's shocking acquittal on October 3, 1995, the country was watching the future of media play out before our eyes.

The trial is still so fresh in the public's mind that, today, over 20 years after the fact, people still freely refer to it as the "trial of the century."

On April 19, 1995, a truck bomb assembled by former Army soldier Timothy McVeigh exploded in Oklahoma City outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. More than 100 people were instantly killed, with more people trapped inside the building, which had partially collapsed. The final death toll rose to 168. The media immediately flocked to the scene, covering every aspect of the bombing and the eventual trial. Due to the intense media coverage, the trial moved from Oklahoma to Colorado, and news stations and reporters were banned from doing closed-circuit telecasts of the trial. McVeigh was convicted of multiple federal felonies and was executed in 2001.

On December 19, 1998, the House of Representatives voted to impeach President Bill Clinton on the counts of perjury and obstruction of justice, charges that came out of a sexual harassment lawsuit.

As the Washington Post’s Peter Carlson wrote in 1999, the impeachment proceedings of Bill Clinton would be, to plenty of folks, the “trial of the century”:

“It will truly be the trial of the century," Alan Dershowitz wrote in USA Today. "It will be the real trial of the century," Tom Brokaw said on NBC News. "Without doubt, the trial of the century," Cynthia McFadden said on ABC News. “Trial of the Century," reads the huge headline on the cover of the Weekly Standard, a conservative magazine. The Independent, a liberal London newspaper, agrees. So does Agence France-Presse. And the New York Post, the New York Daily News, the Detroit News, and the Rock Hill (S.C.) News, all of which termed the upcoming impeachment battle "the trial of the century.”

Clinton was acquitted by the Senate on February 12, 1999, just in time for the century to be over.

When police learned about missing 2-year-old Caylee Anthony in July 2008, suspicion immediately turned to her mother, Casey Anthony. Investigators discovered she had been lying to them during the efforts to find her daughter—about her job, Caylee’s babysitter, and when Caylee disappeared. Eventually, they found Caylee’s decomposed body near the family home. Anthony’s trial began two years later. Cable news channels covered the sensational case extensively; HLN’s Nancy Grace even pejoratively nicknamed Anthony “Tot Mom” during the trial. Anthony was acquitted of the most serious murder charges and released soon after thanks to time served and good behavior, but the media frenzy continued for years afterward.

A version of this story ran in 2016; it has been updated for 2021.